The Lost Art of Letter Writing

Exhibit at the Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center, June 2016–November 2016

Why Write Letters?

“Ever-beloved Mother, far away in the dear homeland, I always think of Mother and tears come to my eyes when I think that the seventh year has begun since I left the dear home of my birth. I am not so attached to America that I should forget the homeland…” –Emma Huhtasaari, Michigan, 1909

Immigrants relied on letter writing to communicate with loved ones back home as well as across their new country. During the early phase of Swedish mass migration, letters written to family back in Sweden were sometimes printed in local newspapers. Many of these letters spoke positively of the immigrants’ new life in America and spurred more people to immigrate to the United States.

Letter writing allowed immigrants to form new relationships with their family and friends across the Atlantic while forming a new sense of self in America. These so-called “America letters” detail an important part of the Swedish immigration story. However, they only offer a fragment of the story, carefully edited by the writer and shared in pieces with recipients many miles away.

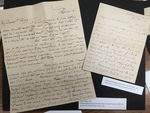

Letters as Artifacts

We can all recognize letters as a particular type of object. We know something is a letter based on its size and shape, the way the address is written, the type of stamp. We can also expect something of the contents based on our knowledge of the sender (is it our mother writing news from home or a loved one penning a heartfelt note?).

Letter writers often used every day, practical language. They had a tendency to write in clichés, repeat phrases and themes from letter to letter, and follow a formula. These tendencies served to make letter writing predictable and allow historians to see patterns across subjects and time. The letter writing formula usually includes a salutation, body, and farewell. The salutation often includes the recipient’s name and clues about the relationship to the writer (e.g. Kära Syster Sara/Dear Sister Sara or Älskade Hjalmar/Beloved Hjalmar). After the opening address, the writer often gives thanks for a letter received and may offer apologies for not writing sooner, the quality of their penmanship, or for having to write a “few lines” before rushing off to another activity.

The body of the letter often includes news of health, family members, and current events. Immigrants often wrote about adjusting to their new circumstances, work, and the environment, as well as their nostalgia for home.

At the end of the letter, writers may sharply state, “I have no more to write.” Then they often greet relatives, ask the recipient to write soon, and offer a final wish for good health before the final salutation and signature.

Positive America Letters

“The ease of making a living here and the increasing prosperity of the farmers, year by year and day by day, exceeds anything we anticipated. If only half of the work expended on the soil in the fatherland were utilized here, the yield would reach the wildest imagination…”

–Pehr Cassel in Iowa to family in Sweden, 1846

Many immigrants wrote favorably of their new home, whether out of genuine satisfaction or to please the reader. Immigrants may have wanted to encourage more people to come to the New World to help with work, offer companionship, and fill congregations. Sometimes, writers also spoke highly of their new life because they wanted to justify their decision to leave.

Negative America Letters

“There are certainly many who write home, but they do not speak about their hardships so as not to worry their people back home…in that way many have been lured on their way. I speak from my own experience.” –an immigrant writing to the Swedish Commission on Emigration in 1908

“…In Chicago we met many Swedes we knew, who have written glowing letter to Sweden but who now can hardly be said to be earning their own bread. So one ought not believe all the favorable letters.”

–Lars Magnus Rapp in Andover to family in Sweden, 1850

Letter writers have received criticism for only speaking about the positives of their new life. However, we know that the immigrants faced many hardships. Some letters described this hardship and condemned others for not writing about the negative aspects of their new lives.

Love letters

“Oh! But I did get lonesome for you after you had left. Driving home from town I just let the horse walk along as he chose. My thoughts were elsewhere. Yes, I did walk along after the train—but could not keep up with it. So I went over to the grocery store and bought some sugar and lemons, the first to represent you—faintly—the other—myself (as I sometimes am). The two together—you know—make not a bad combination.” –Carl Lorimer to Mabel Anderson, 1911

Separated by distances short and long, courtships often happened through letter writing. The Carl Lorimer and Mabel Anderson letter collection documents a four-year courtship, from 1907-1911, through the letter writing of an Augustana Seminary student and a teacher in Ottumwa, Iowa.

Is Letter Writing Really “Lost”?

We may no longer use pens and pencils, but perhaps we still keep up a similar tradition of letter writing in the 21st century. “Letter” writing today often takes the form of email, text messages, Facebook posts, blog updates, or tweets.

What are the similarities and differences between these forms of writing and letter writing of the immigrants’ time?

Does our writing use every day, practical language?

Is it often routine and formulaic?

Does our language change depending on the form of letter writing?

How does each of these venues serve a purpose for the writer and reader?

Check out our digitized letter collections

The Swenson Center has digitized two letter collections.

They are available to browse or search online.

Letter writing station

Take a minute to write a loved one an overdue letter

Sources

“Up in the Rocky Mountains: writing the Swedish immigrant experience,” Jennifer Eastman Attebery. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, c2007.

“Letters from the promised land: Swedes in America, 1840-1914,” edited by H. Arnold Barton. Minneapolis, 1980.

“America, reality & dream: the Freeman letters from America & Sweden, 1841-1862,” Axel Friman, et. al. Rock Island, IL: Augustana Historical Society, c1996.

”Fullständig svensk-engelsk bref- och formulärbok.” Chicago, Ill.: The Engberg-Holmberg Publishing Co., 1896.

MSS P:6 G.N. Swan papers

MSS P:31 Richard C. Holtman papers

MSS P:339 Scandinavian American Portrait Collection

I/O:58 Upsala College records

MSS P:331 Martha Christensson school papers

MSS P:329 Anna Persson Cave family papers

MSS P:251 Charlotte Odman postcard collection

MSS P:258 Mabel Anderson and Carl Lorimer correspondence